Knife Design

“What is the best steel? What is the best shape?”

I get questions like this occasionally when talking to people about knives. The answer to both is “It depends.”

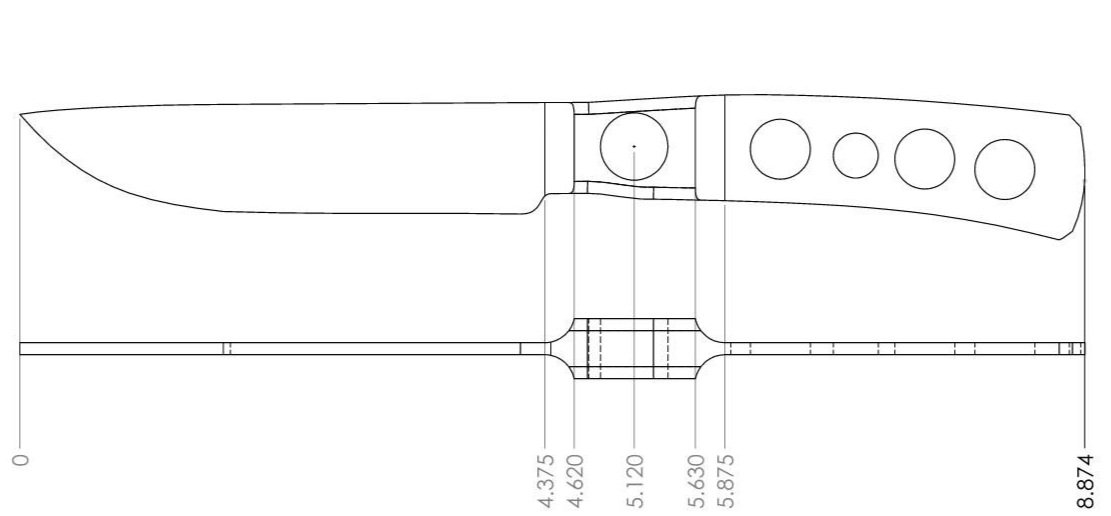

Shape may be the easier place to start. Determining what you want to do with your knife will narrow down what shape it needs to be. No one knife will be good at everything. Even knives made for tasks such as skinning or field dressing can have a variety of shapes, depending on the size of the game, type of game, and where you intend to use the knife. Skinning an animal on the plains when it is 80 and sunny is very different from skinning a reindeer in the arctic with gloves on.

Steel Selection

Once all of these factors have been considered, steel choice becomes more obvious. The race to make better and better modern steels is a fascinating one that yields lots of options for the knifemaker and knife enthusiast. It can also lead to lots of confusion, as there is already plenty of bad information out there on just about everything to do with knives. A common example is Damascus. I get asked a lot if I do Damascus steel knives; I don’t. Damascus steel (Wootz, to be precise) may have been the pinnacle of blade technology at some point roughly 2000 years ago; modern powder metallurgy (PM) steels make it obsolete. Another result of the race for better and better steels are super steels which, while impressive, may be difficult for the average user to maintain. Ultimately knife steel selection will be a balance of desirable characteristics including toughness, hardness, and corrosion resistance, while also taking blade geometry into consideration. I tend to use CPM154, RWL34, A2, and CPM Magnacut. These air air quenching steels whose properties include a good mix of desirable qualities.

Blade Geometry

Blade geometry is an often overlooked aspect of commercially available knives. Proper blade geometry will create a bigger impact in a knife’s ability to cut than steel selection. Blade geometry consists of the blade pattern (shape), type of grind (hollow, flat, etc) and behind the edge (BTE) thickness, among other things. Geometry should be considered carefully; a straight razor with a full, deep hollow grind and a behind the edge thickness in the handful of thousandths of an inch thick is an excellent slicer but won’t hold up to batoning firewood. Similarly the edge thickness of a knife and edge angle makes a considerable difference in the ability of a knife to cut. There is a saying among knife makers and enthusiasts: “Geometry cuts.”

Handle Shape

Another often neglected knife feature is the handle. One would think as the interface between the human and the tool, the handle, would receive an enormous amount of scrutiny; yet handles that are too thick, poorly shaped, too short, or can only be held in one specific position are common. The handle should also be designed so the user knows the orientation of the knife without looking at it. As an example, some fighting type mass produced knives have cylindrical handles that would not inform the user as the to direction of the blade edge without first looking at it. This should be avoided unless the blade is an ice pick.

Handle Material

Another question I get sometimes is about using certain types of handle materials. Generally I like to use micarta. It is fairly stable, easy to machine, and doesn’t have a tendency to crack, even after repeated exposure to moisture. I also like using certain hardwoods like ringed gidgee as well as some stabilized woods.

Knife Features

Most of my knives will have some features in common. These may include:

Sculpted Plunge Lines

The transition between the ground section of the blade and the ricasso, the flat part past the handle, is called the plunge line. I grind my blades and plunge lines free hand, as it allows me to sculpt and blend this area. Mass produced knives generally feature more squared off or even sharp corners here; those sharp edges are stress risers, and if the blade breaks, theres a good chance it will break along that sharp edge. These plunge lines are also just good looking.

Mirror Polish

The surface finish of a blade has a direct correlation to its corrosion resistance. The smoother surface also helps reduce drag when cutting. Mirror polishing is incredible time intensive, and requires hand sanding and buffing. Buffing is thought to be one of the most dangerous parts of knife making, as the buffer can grab the knife and throw it at high speed if done incorrectly. In addition, high quality sandpaper is required for sanding higher quality steel.

Tapered Tangs

Tang tapering is a time honored tradition among knife makers. While reducing weight in the handle, it also adds a distinctive look to the knife. As a knife maker, nothing says you’ve got time to burn quite like complicating the handle geometry with the addition of a symmetrical distal taper to the handle. This taper is ground in by hand.